Courses and Information

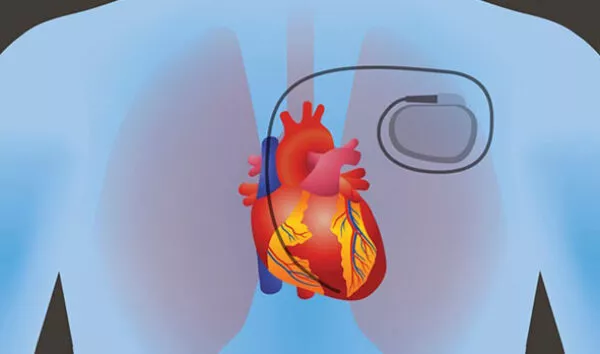

One of the most common questions received by the Academy’s Clinicians Hotline is about how to work with a patient requesting aid in dying who has a pacemaker and/or internal defibrillator. The answer is different for each one.

In general, pacemakers should not be turned off before an aid-in-dying procedure. Turning the pacer off puts the patient at risk of an un-paced bradycardia with associated dizziness, weakness, altered level of consciousness or, at worst, an unpleasant death. Any of the above can interfere with the patient’s planned aid in dying. This is especially true if it’s a continuous pacemaker rather than just in “demand” function.

But will the pacemaker interfere with death from the the aid-in-dying medications? Theoretically, that’s possible, if the patient is dying solely from a medication-induced bradycardia. But that is quite rare. Most commonly, the digitalis and amitriptyline severely damage the heart muscle, preventing the pacemaker spike from capturing the myocardium and creating effective beats. What has been seen with EKG-monitored aid-in-dying patients with pacemakers are pacer spikes without myocardial capture. Essentially, the pacemaker has been chemically disconnected.

Summary: Do not disconnect or stop pacemakers before the aid-in-dying day or during the procedure. Advise the patient that, rarely, the pacemaker may slightly prolong the time to death, but the patient will remain unconscious and comfortable.

For pacemaker/defibrillator (ICD) combinations:

Since the digitalis/amitriptyline combination can cause tachyarrhythmias (and they often do), there’s a significant chance that the ICD will fire and the patient’s unconscious body will jump slightly from the discharge. This may be esthetically unpleasing, even frightening, for loved ones who are present. But the defibrillator firings will not significantly delay the death—the myocardium is so chemically damaged by the medications that the defibrillator is very unlikely to restore a functioning rhythm, and if it does that will be for a very short time.

After receiving extensive clinician input about this, the Academy recommends explaining a choice to these patients and their families: If the family won’t be upset by seeing that slight jump (especially if there’s a clinician there to reassure them), then it’s safe to leave the ICD turned on. But if there’s any question about upsetting the patient with the thought of the defibrillator’s discharge, and/or if the family will be upset, it’s not very difficult to call the company and have a technician sent out a few days before the death to turn off the ICD function (but not the pacemaker component).

For both pacemakers alone and pacemaker/ICD combinations, it’s fine to do nothing and proceed with aid in dying as you otherwise would. But if you can turn off the internal defibrillator (ICD), that’s often a good choice.

Some patients who are not terminally ill and have pacemakers implanted decide to turn off their pacemakers to achieve a less than 6-month prognosis to qualify for aid in dying.

These patients have approached aid-in-dying clinicians saying, “I have the right to turn off my pacemaker, and that will give me a less than six-month prognosis to live. So I’ll do that, qualify for aid in dying, and die that way.”

There are many points of view about how to respond to these requests. But before delving into a response to the patient, it is crucial that a clinician first explores the reasons for and functions of the pacemaker that individual has. That most commonly means reviewing the medical records from the time the pacemaker was inserted, often many years ago.

Many patients have pacemakers inserted because the patient has sick sinus syndrome or other sinus node dysfunction (tachy-brady, etc.). Modern pacemakers have been inserted for “chronotropic incompetence” in which the heart rate doesn’t respond to exertion appropriately. Then there is atrioventricular block of varying degrees, from occasional dropped beats with mild symptoms, to third-degree (complete) block with severe dizziness and/or syncope. Some patients with heart failure have pacemakers implanted to coordinate cardiac chamber contractions.

When a patient asks to have their pacemaker turned off, it is essential for them to understand why the pacer was placed and what is likely to happen if it is stopped. Many patients with pacemakers do not know the answer to either of those questions. So when they come to an aid-in-dying clinician saying they’ll turn off their pacemakers and then ask for aid-in-dying medications, it’s the clinician’s job to provide accurate and detailed information before entertaining the possibility of aid in dying. The range of results from turning off pacemakers varies from a rapid (but uncomfortable) death from severe bradycardia, to a long life with unpleasant cardiac symptoms.

For patients who had their pacemakers inserted to aid with mild symptoms, it would be difficult to say that if they turn off their pacemakers they will have a less than six-month prognosis to live. They do not qualify for medical aid in dying. But let’s say that a patient had a pacemaker inserted ten years ago for complete heart block with a ventricular escape rhythm of 30 to 40, accompanied by dizziness, weakness, but not syncope or death. It is reasonable to conclude that if their pacemaker is turned off they will have fewer than six months to live. And during that interval, they may be very weak and uncomfortable, so medical aid in dying might be considered.

A note of caution: Before turning off a pacemaker to accommodate an aid-in-dying request, be certain what symptoms the patient may experience — from mild chronic dizziness to sudden death and many other possibilities. If you turn off a pacemaker to accommodate aid in dying, be sure the patient will maintain the mental and physical capacity to complete the procedure.

Please see the section below about the possibility of chemically turning off a pacemaker utilizing the aid-in-dying procedure itself.

When a patient says they’ll turn off their pacemaker and thus qualify for aid in dying, the clinician’s response must be based on detailed information about the patient’s underlying cardiac abnormality, the reason the pacemaker was placed, and the likely outcome of turning off the pacemaker—before considering whether the patient may qualify for aid-in-dying care.

Here’s where it gets controversial: Can a patient say they’ll turn off their pacemaker and have medical aid-in-dying based on that request alone?

There are many opinions about this possibility. Here’s an example: a patient’s pacemaker was inserted ten years ago for complete heart block with a ventricular escape rhythm of 30, accompanied by dizziness and weakness, but not syncope or death. If their pacemaker is turned off they will have fewer than six months to live, and during that interval, they may be very weak and uncomfortable, so medical aid in dying might be considered.

Might it also be proposed that the patient’s request to turn off the pacemaker indicates they have a less than six-month prognosis to live, qualifying them for aid in dying? And if the patient wants to avoid the severe dizziness and risk of syncope (and loss of mental competence for aid in dying)—might it be possible and legal to move forward with medical aid in dying while the pacemaker is still in place and functioning?

In such a scenario, the patient—with the pacemaker still functioning— takes aid-in-dying medications and enters a coma, at which time the hypoxia, digitalis, and amitriptyline chemically turn off the pacemaker (lack of myocardial capture), which is what the patient requested. In this case, turning off the pacemaker and aid in dying are achieved as a unified procedure.

NOTE: The Academy is not recommending combined pacemaker stoppage and aid in dying. Some aid-in-dying clinicians have performed this procedure. Others condemn it. There is no known consensus, no established best practice or standard of care. It is up to each aid-in-dying clinician to carefully consider the medical, ethical, and legal components at play, and make their own decision for each individual patient.

IF YOU ARE WORKING WITH SUCH A PATIENT, PLEASE CONSIDER BRINGING THE DILEMMA TO THE ACADEMY’S ETHICS CONSULTATION SERVICE.

Qualifying a patient for aid in dying by their request to turn off their pacemaker, and then turning off the pacemaker chemically during the aid-in-dying procedure, is controversial. Each clinician must make their own decision about the legal, ethical, and pharmacologic considerations.